|

Heavy Weather  The

amount of thought that must be

given

to preparing for heavy weather is out of proportion to the number of

times

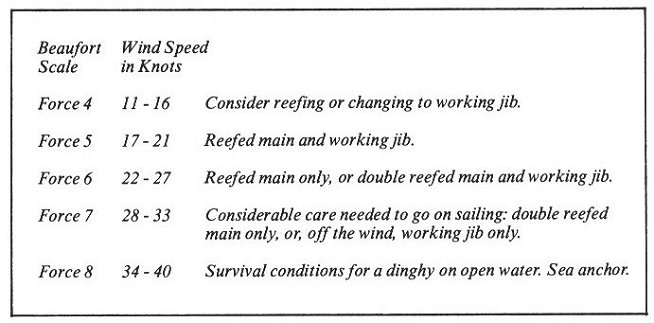

you will encounter it. You may expect to be out in Force 5 winds a few

times on a cruise even if you listen to the radio and avoid going out

when

strong winds are forecast. I would not call this "heavy weather",

however.

Force 5 winds normally require a reef, and probably a change from the

genoa

to the working jib. This should become an easy routine through

practice.

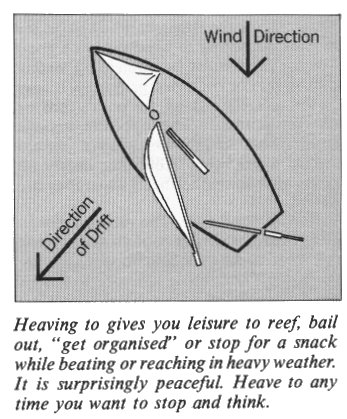

Often it is best to reduce the jib first before the sea gets up. Some people find a jib down-haul helpful. To make one, run a piece of line through the piston hanks from the head down through a shackle on the bow fitting and back to a cleat. The line is also handy to tuck the sail under when it is down. Head-shackle and all piston hanks can then be easily reached and the crew can lie on the fore-deck for all the finger work involved. The helmsman can control the halyard. Once the working jib is up, if the wind continues to increase and you need a reef, the easiest procedure is to heave to. This can be done by pulling the jib across to windward, or by going through the motions of tacking but leaving the jib on the new weather side. (Al's note: I

have tried

the latter method twice and found it too violent. I now always heave to

as follows With

the main-sheet adjusted, the

centreboard

raised one third and the tiller held down to lee with a shock cord, the

dinghy will be quite peaceful, bobbing on the waves, making some leeway

and heeling very little. Now you can easily reef the main. With slab or

jiffy reefing, it is easiest if you heave to on the tack that leaves

the

boom fittings on the weather side. The procedure is to slacken the main

sheet, haul in the leech line and cleat it, then let off the halyard

and

haul the luff line until the luff cringle is close to the boom, and

secure

it. Another pull on the leech line brings the leech cringle down to the

boom. The halyard is then tightened and secured, the mainsheet can be

hardened

in again, and while still hove-to the reef points are tied along the

boom.

Let go the weather jib sheet, and you are underway again.

(Al's note: For more on Jiffy Reefing click here) .  (Al's note: If

you

want even more peace while hove to, make sure that you vang the main.

This

not only reduces wear on the main leech, but also reduces the

nerve-wracking

flapping sounds. Board full up increases the rate of leeward drift but

has two benefits:

In a

20-knot breeze, which makes racing

exciting,

a dinghy laden for cruising and reefed to 70% of mainsail area can be

sailed

comfortably with no particular concern about the weather. We do not

usually

hike out, but sit on the gunwale with sheets in the hand. You have

probably

got plenty of time to get to shelter before the wind strengthens

further;

if not, you can take down the jib altogether. It is rarely necessary to

do more, but if it is essential to go on sailing in still stronger

wind.

You may have to use the second reef points in the main, and thus reduce

sail still further. It may be necessary to bring the sail down entirely

in order to add roller reefing over an existing Jiffy reef. Try this

out

to be sure, before you need to do it in a strong blow.

Sail

balance is important.

The likeliest

cause of a broken rudder is fighting a weather helm in a strong blow,

especially

if a tired shock-cord allows the rudder to swing part way up. Instead

of

fighting it, ease the mainsheet before anything breaks, check that the

rudder is fully down, and then consider whether you should take any of

the following actions which reduce weather helm:

If,

on the other hand, there is lee

helm while

sailing to windward in a good breeze, there must be something wrong

that

should be corrected promptly. It may be the sails, the rigging, the

boat's

trim, or the centreboard. The opposite actions from those mentioned

above

would reduce a lee helm. Note that nearly all boats have a weather helm

when they are heeled to leeward.

Al's note: The

faster

the boat goes through the water, the more the angle of heel affects

your

helm. Remember that while the boat is moving forward,

Reef

in good time. The racing

sailor

in gusty weather carries enough sail to keep full speed in the lulls,

and

hopes to survive the puffs. The cruising sailor, on the other hand,

should

reef so that he sails comfortably in the puffs, and should not be

concerned

about loss of speed in the lulls.

Sailing in the lee of a hilly shore is a situation where you should shorten sail early to reduce the risk of capsizing. You may get very sharp gusts with a downward element in them. Thunderstorms can also pack dangerous gusty winds with strong downdrafts. The trouble with a downdraft is that it does not spill over the top of the sail when you heel far over, as the level blow of a strong wind does. Keep a look-out for thunderstorms, and if one hits, lower all sail until you see what it is going to do. Alternatively, if you feel confident, you can carry on with reduced sail but have the main halyard ready to let go, and be sure that it will run free. Hold the jib sheet in hand, ready to release. Flapping sails in a strong squall only make a terrifying noise; the only danger lies in a turn of the main sheet round your ankle, a jib sheet caught on a cleat, or a halyard that tangles and jams. Al's warning: I

have to beg to differ here. On at least two occasions, I have capsized

in thunder squalls - slowly but surely - when the wind resistance of my

flapping sails made the boat heel more than we could hike flat

whereupon

the wind got under the side of the hull and flipped us the rest of the

way over. My son and I also very nearly capsized in a squall that hit

the

fleet during the 2001 Canadian Nationals when we did not get the sails

down before the nasty stuff hit. What saved us was my diving to jam the

board full up. This gave me enough of a breather to get the sails down.

After that, we just sailed along "under bare poles" with the board half

down and maintained reasonable control of where we were going - always

generally downwind, of course. If I were cruising and saw anything that

looked like a squall coming, I would always take my sails down good and

early - or if there was little sea room and a shore to leeward which I

did not wish to hit, take down the jib and reef the main as much as

possible,

and try to sail my way out of it.

There will be no big waves in a sudden sharp blow and there is no great need to keep head to wind if your sails are down. If you are temporarily lying across seas with breaking tops, lift the centreboard to avoid the tripping action that can occur when the hull is carried along by a wave top while the board is down. When the wind has been blowing for a few hours and strengthens too much to carry any sail, it is essential to keep head to wind and sea. The sea anchor or drogue is the proper equipment for this. If you carry one, practise using it in a moderate wind. Be sure you know how it will go out, how the line will be led, and how it will be secured. Remember to unship the rudder, as you will be drifting stern-first. The actual pull in a dinghy is not terribly hard and you do not have the problems that cruising yachts have with regard to strain on the sea anchor and its rode. The rode needs a swivel, and should be a good one; we use a spare jib swivel shackle. This is fixed to the bitter end of the Danforth anchor rode, and it is normally snapped to the standing part around the thwart. For the sea anchor we use the rode in reverse, snapping the swivel shackle on to the yoke of the drogue. You need a good bow chock, with overlapping horns. (This is also important if you are being towed.) Everything should be arranged so that the sea anchor is easy to use. When you are in a survival situation, it is not safe trying to do something difficult that you have never done before. You may be forced to, but it is better to plan ahead. An alternative to the drogue is to float the mainsail out on its boom from the bow and allow the boat to drag to the lee of this. The sail is said to smooth the waves as well as hold the head of the boat to windward. If you plan to use this method, it is important to practise it and to be sure how you will secure the yoke to the two ends of the boom and to a stout line running to the boat. This would be difficult to improvise at the time it is needed. It is of course important not to lose your mainsail, as you will need it to get back to shore after the gale. If possible, double the rode. Once you have the boat head-to-wind and everything is secure, it is time to think about chafing gear at the bow chock and any other place where the rode may chafe. "Freshen the nip" occasionally. If the boat does not come head to wind lying to the drogue or to the mainsail floated out, you may have to improvise some windage near the stern. An alternative is to lower the mast, which may be desirable anyway to increase stability. You may lower the mast onto the boom crutch if you know it will fit. Otherwise the mast can be lowered on to a pad of fenders, etc. on the afterdeck or transom. It must be secured laterally, otherwise the leverage as the boat yaws and rolls will severely damage the tabernacle. During the lowering process, there is a risk of just this accident. Choose a relatively smooth moment to do the lowering. Now, having the boat head to wind and sea, the mast down, and chafing gear fitted, there may be wave tops coming into the boat. Some sort of cover, even improvised with a sail, should help. We have had a special cover made for this duty, and it doubles as a shelter so that the watch below can sleep during night sailing. For shelter while sailing, the cover fits over the fore part of the cockpit as far as the centre thwart, and is held up (but clear of the boom) by a boat roller on end. With the mast down, however, the cover goes right over the mast and shelters the forepart of the cockpit. I should emphasize that all these preparations are not necessary for dinghy cruising in sheltered waters, or when shelter can be reached within an hour or two. For fierce winds of short duration, such as summer thunderstorms, the waves will not be big enough to endanger a stable dinghy. Wind alone is not likely to capsize a dinghy with all sails down. To sail in a fresh breeze, and to go safely offshore at all, the essentials are:

The

boat and rigging should be tidy and

orderly,

so that sheets run freely when released and halyards run freely at

need.

A spinnaker is a dangerous sail to have flying in gusty winds and

stormy

conditions.

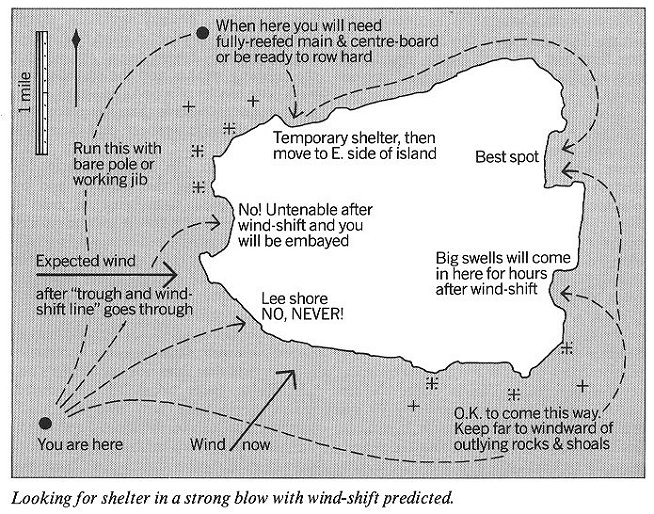

If a full gale is forecast you should not be sailing out of reach of shelter. Preparations for lying to a sea anchor should only be necessary if you are planning a major open water crossing. Strong winds of long duration can always be forecast at least several hours ahead, so always try to get a weather forecast before embarking. Lee Shores. A "lee shore" is one towards which the wind is blowing. A "weather shore" is one where the wind is blowing off the shore towards the lake or sea. The difference, on a windy day, is quite astonishing. Take a look at this from the land any time you are near a lake, and think how it will affect your planning when you cruise. When

looking for shelter from severe

weather,

it is important that you do not commit yourself to beaching on a lee

shore,

where the breakers would certainly destroy your boat. Keep this in mind

when planning the day's trip. If there is nothing but a rocky shore

which

is likely to become a lee shore in a blow, you will sail along it at

your

peril. A deep cove in it might provide shelter, but the entrance is

often

dangerous. Off-shore islands can provide some degree of shelter, but

rocks

in the approaches, easily seen and avoided in good weather, are a

lethal

hazard off a lee shore in a blow. When coming for shelter it is

important

to know where you are and to read the chart carefully to see where you

can safely approach. If you can get into the shelter of a headland or

island,

and row or beat up to a weather shore, you will find it a marvellously

peaceful place to be in a strong blow. .

Tacking.

In strong winds, wind

and

sea may stop the boat as she comes head to wind. Avoid this by sailing

a few degrees below closehauled to attain maximum speed, choose a

relatively

smooth patch, push the tiller down (leewards) firmly, sheet in the main

tight as she comes up, and have the crew hold the jib momentarily on

the

new weather side to help pay off quickly. If caught in irons, reverse

the

tiller as soon as the boat starts to drift astern. On the new tack,

ease

the main sheet and steer a little low until you pick up speed.

Gybing. Gybing may be the safest method to come about in very heavy winds. Turn downwind, with the centreboard up. The boom vang should be attached (and the crew must keep clear as it sweeps across the boat). With the boom right out, put the rudder hard over and sail more and more by the lee, until the wind is almost abeam. Do not help the boom across, but wait for the wind to do it. After the boom comes over, the sail will be almost empty of wind, and can be sheeted in gradually. (Uffa Fox suggested this method in his book The Crest of the Wave.) Al's note:

The "put

the rudder hard over" part of the above makes me nervous. I would

suggest

the S-gybe as outlined in my article Miscellaneous Manoeuvres. More

gybing details are also given just past half-way through the TSCC Guidelines for Inexperienced Wayfarers.

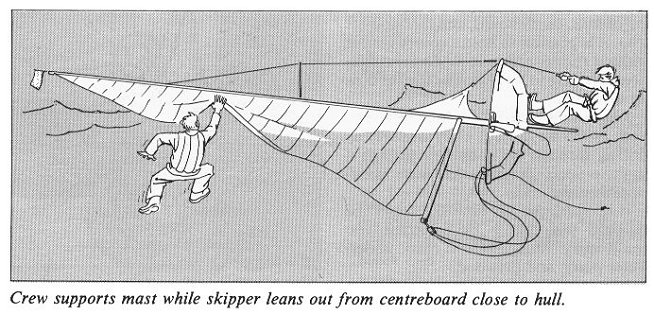

The helmsman should assist the mainsheet across to prevent it from fouling on any projection. I have faired the ends of the rubbing strakes and the traveller rail with little blocks of wood and epoxy resin, so the rudder-head is the only place that could catch the mainsheet, and there I lift it over. Capsizing. You can avoid capsizing by carefully watching the weather and by reefing in good time. Just in case it happens, the drill is this: First, be sure to grab a line (if you do not have a safety harness), and do not swim after floating gear. The boat may be drifting faster than you can swim. Never, never leave the boat and try to swim ashore. To

right the dinghy, stand on the

centreboard

near the hull and lean far back holding any line that does not impair

the

sails. The crew helps from the masthead, manoeuvering the bow into the

wind, pushing upwards on the shroud and working his way towards the

boat...

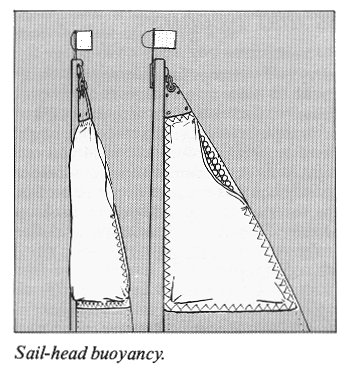

If

there is no masthead flotation, the

skipper

must not climb up and over the high side to get to the centreboard but

swim around. And the crew should stay clear, buoying the mast and thus

avoiding being trapped under a turtled boat. ...

Al's note: With all due respect, I have vast capsize experience and would recommend some simpler methods as outlined at WIT/SelfRescue.html. I personally don't like the thought of sending the crew out swimming to the mast head, etc. Only

when there is leverage on the

centreboard

should any attempt be made to release the main halyard. (This is a last

resort in getting the dinghy upright.) To keep a swamped boat pointing

into the wind the crew goes to the bow and lets his body hang

vertically,

acting as a sea anchor. (He may have to push himself down to counteract

the buoyancy of his life jacket.) The

skipper will clamber in as the

dinghy

comes up, (watch out she doesn't roll over with his extra weight, to

the

opposite side) and, if necessary, jam a sailbag or shirt into the

centreboard

trunk. Then he

starts bailing hard. (The

bailer was

firmly attached by a line, remember.) Two hundred good heaves makes the

craft stable enough for the crew to come aboard. A short spurt across the wind with auto-bailers open will empty the craft of water. Capsize your dinghy, weighted as if loaded for cruising, in home waters, if you have never done so. Get the feel of these various manoeuvres and acquire a confidence that you can right her, bail out, and go on sailing. Lightning Protection. In a two-week summer sailing vacation, you can expect to encounter one or two thunderstorms. Very rarely do they do any damage, but they can be alarming, and the possibility of a lightning strike is always present. Only once have I seen a dinghy struck by lightning. The skipper and crew were unhurt, and the damage to the dinghy was repairable. There

is no reason to suppose that

lighter-gauge

conductors would be less effective on a dinghy than those that are

required

on a larger boat. (See C.P.S. and Government publications for

recommended

conductors.) The full precautions may not seem feasible. We clip auto

"jumper

cables" to the shrouds, and hang them in the water, and we are careful

to keep well away from the standing rigging during a thunderstorm. An

aluminum

cooking-pot hung from the jumper cable increases the grounding

area. |