|

"Where Vikings Once Roamed"

A tale about Wayfarers sailing the Irish Sea by Dick Harrington copyright © 2002 |

|

The foot passenger gangway leading off the ferry was long and completely enclosed, making several sharp turns along the way. Hauling three weeks worth of luggage in addition to the necessary sailing gear for an open sea voyage was no picnic. From inside the tunnel one lost all sense of direction, but at the end Scotland awaited. In the past 48 hours my wife, Margie, and I had been to so many places and so much travel had already transpired, that my head, if not Margie's, was swimming. My ability to concentrate on the immediate objective was obviously dulled. It's no wonder then that I was startled. Bursting forth at last into dazzling sunlight I bumped smack into Alice Tyrrell's bright smiling face and her cheerful, "Welcome to sunny Scotland!" Quickly as I could I gathered the tiny Welsh lady into my arms and laid upon her one of my biggest and best kisses--words for the moment eluding me.

It was Saturday, August 4, 2001. The day before we had arrived in Dublin after leaving Cleveland, Ohio on Thursday afternoon. Catching a couple hours of rest we were out again to enjoy the sights in Dublin and take in some great traditional Irish music at the popular and locally famous "Gugarty's Pub". Then Saturday morning it was off for the train to Belfast and the high-speed ferry to Stranraer, Scotland which departed the Belfast terminal at 1700 hours.

None of this would have come about if it were not for the good folks of Northern Ireland at the East Down Yacht Club (EDYC), their generosity, and their dedicated efforts. Located on the shore of Strangford Lough near the town of Killyleagh, EDYC was hosting the 2001 Wayfarer International Championships. Preceding the week-long racing activities would be the International Cruising Rally, a gathering of cruising minded sailors from all across Ireland, the UK, Scandinavia, Holland, Canada, and the United States. There would even be one boat from the tiny Isle of Man. Many are long time close friends.

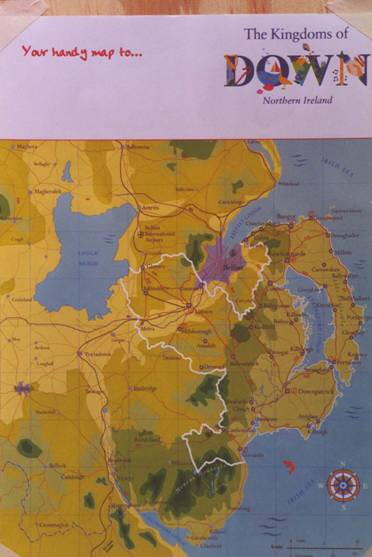

Strangford Lough is a very beautiful natural inlet of the sea, approximately 20 miles long by 5 miles wide, located on the Belfast Coast of Northern Ireland in County Down. It is surrounded by high hills of greenery and picturesque villages, with many magnificent castles and cathedrals dotting the landscape. The waters contain a multitude of islands and it is one of the world's largest wildlife bird sanctuaries. As an ancient maritime highway various peoples--the Celts, Vikings and Normans--traveled, traded and fought over the land for the last two millennia. Its surroundings brim with historical artifacts and legends, with monuments and ruins dating as far back as 500 BC. The name Strangford is Viking, meaning angry waters. The usually brisk winds, combined with the lough's ever present strong tidal currents can, at times, make for challenging sailing--a characteristic obviously not overlooked by the Vikings. Margie and I had been planning this trip for a year. All together the rally, and the championships, promised to be an outstanding affair with as many as 200 people and over 100 Wayfarers expected to attend.

Besides participating in the rally with Margie (we were not racing) I had been offered a special invitation--the chance to be part of an advance feeder cruise being planned by two British Wayfarers. The cruise would entail crossing the Irish Sea from Scotland to Northern Ireland, then sailing down the Belfast Coast and into Strangford Lough. Our arrival at EDYC would be timed to coincide with the start of the first day's rally activities. I would crew for my friend Dick Tyrrell on W7241 - "Yellow Misfit". The Tyrrells live in the quaint village of Ashurstwood, not far from London. Margie and I had became close acquaintances with Dick and Alice during the International Cruising Rally held on the Norfolk Broads in England the summer of 1999. At first it hadn't fully registered with me, but as the cruise materialized I came to realize what a terrific opportunity this was--to sail, if only in a small way, the ancient pathways of the Vikings.

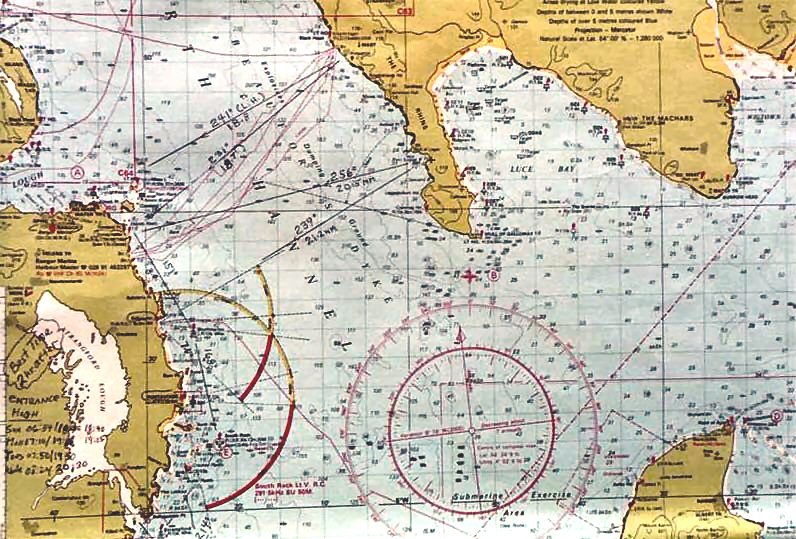

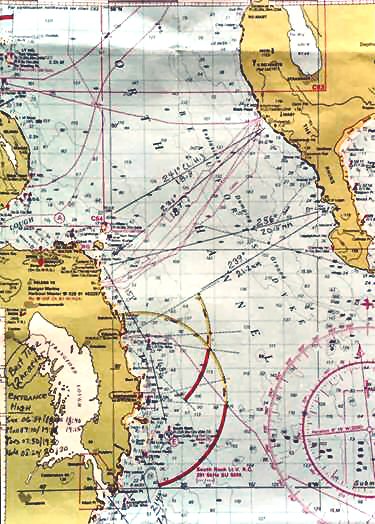

Taking advantage of the two-hour train ride from Dublin to Belfast I spread half a dozen charts of the Irish Sea upon the table in our booth. It was time to get serious. Meanwhile, ignored by me, Margie fretted over the potential consequences of disregarding the U.S. State Department's advisory against travel into Belfast. The north bound train, following the coast a short distance inland, passed through occasional showers. But every now and then the sun would pop out briefly from behind the clouds, revealing a countryside as lush and green as the "Emerald Island" so often boasts about. It sparkled with a freshness that we parched midwesterners from the U.S. drank in to the fullest. The cool 70-degree temperature was a delightful relief from the oppressive heat and dryness we had left back home. Arriving in Belfast, to add to Margie's already nervous state, travel immediately became a mystery as we had no idea how to get from the train station to the ferry terminal. Fortunately, and just in the nick of time, two fellow Irish train travelers on a holiday trip took us literally by the hand, while carrying half of our bags, to the proper bus station. Frayed nerves were in need of soothing with a pint of Guinness at "Robinson's Pub", suggested by our benefactors thinking that they might later join us while we waited out the two hours for the bus to the ferry. In retrospect it was probably best that the bus arrived first.

By the time we were leaving Belfast Harbor the huge HSS Stena, an impressive jet propelled ship, was planing at 40 knots on a heading northeast by east destined for Stranraer, Scotland. The crossing would take just under two hours. Not one to miss a golden opportunity I hurried to the forward windows (no open decks on this vessel!), again with charts in hand, seeking to gain some familiarization. Off the starboard bow was a high lighthouse, Mew Island Light. At 24 meters tall, except in the worst of weather, it should be visible day or night for much of our sail across. A small group of islands near the southern headland of Belfast Lough, marked by Mew Light, needed to be avoided as it is an area of strong tidal currents. Unable to restrain myself I insisted Margie come over while in skipper fashion I pointed out my observations. It was a rare moment when she actually seemed to exhibit an interest in charts--maybe mostly to please me. On the other hand I suspect that all of the lead up planning she had been exposed to and the awareness she had of the dangers had some bearing on the matter. The open sea crossing we would be making was actually at the Irish Sea's narrowest girth, only about 19 nautical miles across. Still she had heard enough to frighten her. Another rain shower closed in, temporarily obliterating any further viewing of the Northern Ireland coast. Fickle and true to form for this part of the world, by the time we reached Scotland the sun was again shining brightly.

"Graeme is with me in the car park, but Dick T. is back at the boats with Pam trying to get things squared away." I had voiced a question to Alice as she seemed to be alone. Graeme and Pam Geddes would be our companions in the other boat, sailing their Wayfarer World, W10080, "Angua"--"named after the female werewolf in a Terry Pratchett novel", says Pam. Also British, they were currently living in Glasgow, Scotland and would be the lead boat on the cruise--Graeme being the UK Cruising Secretary. Wasting no time our luggage and ourselves were piled into the Geddes' vehicle, as the Tyrrell's Landrover was crammed floor to roof with camping gear with hardly an inch to spare. It was getting late and time was precious if we were to have dinner. Hurriedly, we headed down confusing one-way streets through the small port town of Stranraer, searching for the winding narrow coastal road leading to Port Logan--a seaside village 25 kilometers to the south. In the confusion, unfortunately, Alice who was following a bit too far behind missed one of the tricky unmarked turns. Lost was the chance for dinner at Port Logan's one and only pub, which shut down promptly at 8:00 PM without pity upon tardy strangers. So alas, it was back to Stranraer and a late night fish and chips shop--the UK's answer to "McDonalds".

The Britons' original plan contemplated departing from picturesque and closer Portpatrick. However, as things would have it, Portpatrick on this occasion turned out to be busy and crowded with holiday visitors. So it was abandoned in favor of the much quieter and practically deserted beach of Port Logan. Port Logan is mostly open to the sea with maybe a dozen houses, plus one pub, scattered along its broad shallow horseshoe-shaped bay. Partial protection is afforded by a stubby thick breakwall against the prevailing and sometimes strong southerly winds. With a long and gently sloping beach this is an excellent launching spot, as long as the winds are not too strong onshore. While Graeme and Pam spent the night on the beach in their Wayfarer, true to the spirit of Wayfarer cruising, the rest of us, Margie, myself, and the Tyrrells, copped-out for the B&Bs in Stranraer, preferring one last chance for a good night's sleep and a hearty breakfast in the morning. But sleep had been slow to come as the pre-cruise jitters nagged at our consciousness. Was Graeme correct to be concerned about the possible ill effects of jet-lag on his American friend? And Margie of course worried if she would ever see the "two Dicks" again. Nevertheless, when morning arrived with a promise of fair weather our spirits were buoyed and I was feeling fit for anything.

"We depart - weather permitting." How many times had Margie and I heard (read) that phase from Graeme and Dick T. But we understood. The Irish Sea was not to be taken lightly. It can be vicious and its notoriously strong tidal currents have caused many a mariner to come to grief. As far back as the discussion and planning stage we had been concerned about the prospect of being stranded by bad weather on the Scottish coast, unable to sail and ticking lost holiday days off the calendar. So when Sunday arrived bringing with it a fine weather window, a forecast for partly cloudy skies and moderate southerly winds, everyone was greatly relieved. Margie and Alice could feel comfortable sending us off, then taking the car ferry back to Ireland knowing with reasonable assurance that by evening the two small boats should safely be on the other side as well. It was a grand departure with the six of us almost gleefully jogging the fully laden boats down the hard sand and into the icy sea, with fanfare and a splash. All the while Margie's camera was capturing many action photos to accompany the stories later. I was thrilled and excited. My English counterparts had selected a marvelous location and the weather was cooperating perfectly.

Pictures on travel posters, calendars, and the like, of the Scottish seacoast frequently show vistas of spectacular seascapes, often starkly bold and mountainous, with rough seas breaking over treacherous rocks. I remember admiring a splendid photo of a castle perched precariously on the side of a steep precipice with the sea below. The southwestern coast of Scotland from which we embarked is not so wild and rugged. Nevertheless, it is a magnificent coast dominated by high rolling hills with green pastures and steep bluffs, and with cliffs easily a hundred feet high that drop abruptly into the sea. Interspersed here and there between shear-walled cliffs are harbors and bays, sometimes with broad sandy beaches. Once out to sea on this bright sunny day I couldn't help but marvel at the beauty of the Scottish coast, though I was seeing but a tiny piece of it. I was 'burning' a lot of film. I also quickly became aware of something else, the presence of many sea birds around us, mostly varieties unfamiliar to me. This was one of many facets of the cruise that I previously neglected to think about. Soon the antics and acrobatics of the sea birds had me fascinated, capturing much of my attention. Thus, if the wind began to slacken and sailing became slower, I didn't take much notice.

Unmercifully, I pestered the Skipper for names. The miniature duck-like swimmers paddling in groups with the bright pink razor type bill were a variety of Auks. Teasingly, they would let the Wayfarer get just so close, then go skittering off across the waves. The dark, sleek speedsters with long wings, skimming only a couple of inches above the waves, were Shearwaters. The dive-bombers, with an all white body except for black tipped wings, looked like a gull from a distance, but were a variety of the Petrel. The petrels would catch their prey by dropping straight down from up high, knifing into the sea creating a tall geyser rooster tail.

Sometimes, when finally out to sea after much last minute rushing about, I have a gnawing feeling that something has been overlooked. If neither of the "two Dicks" had this feeling we should have. Quickly we fell into a comfortable sailing routine, the going being much easier than expected. The state of the sea was a moderate chop, with an occasional small whitecap, but no noticeable underlying swell. It wasn't a whole lot different than some of my experiences on the northern waters of the Great Lakes back home. With sails trimmed close-hauled, the southwesterly breeze combining with the southerly flowing ebb tide, lee-bowing us, was just enough to allow a fair heading on the Belfast coast. It would be a fetch, for most, if not the entire way across. This was not by accident as Graeme had carefully planned the crossing and timed our departure to take advantage of the strong tidal current. So if the wind took us too much to the north, the tide would compensate by setting us back. Additionally, my Skipper had done well getting "Yellow Misfit" organized ahead of time. There was little of the normal dishevel and confusion, with items not yet properly stowed, that often accompanies the start of a cruise. The two of us had agreed ahead of time to "go light", for the sake of safety and speed, and not bring anything we really didn't need. An example of our Spartan thinking was the conscious decision to "get by" on cold meals and not bring a stove. The Geddes' would have a stove (they would be continuing on for an extended cruise afterward) and we knew we could get hot water for coffee and tea from them. With everything so fine what could go wrong?

A couple of miles off the Scottish coast our nice breeze began acting fluky. From time to time it would appear to die down, then just as I was getting concerned it would pick up again. On one such occasion we were abruptly awakened by the alarming sound of screws tearing out of wood and fiberglass. The mystery lasted but a split second, as the mainsheet jammer immediately parted company from its mounting on the back of the centerboard trunk, leaving the sail and boom to lurch off to leeward. Shocked, I may have let go an expletive.

I need to explain that for a Wayfarer "Yellow Misfit" is equipped with an unconventional mainsail sheeting system. There are no blocks at the end of the boom and on the transom. All the sheeting runs through double blocks mounted on the jammer, which is located on the after side of the centerboard trunk, and to the center of the boom. The advantage of this arrangement is that the cockpit is kept clear and the chance of hanging a sheet around a motor, or transom corner, is eliminated. One disadvantage is that it is impossible to effectively center the boom in the boat, which reduces the ability to point to windward. Another problem is the much greater loading placed upon the jammer and its mounting. The fastening of the jammer needs careful consideration. Dick T. and I had discussed looseness in the jammer mounting before departure, but he believed it to be okay, while assuring me that he had a backup plan should it fail. Now the truth was known.

"Hey 'matety', don't you worry, I've got the situation covered", was Dick T.'s nearly instantaneous response. It was a moment where I hardly think I believed such talk. The situation certainly looked dire and the feeling in the pit of my stomach confirmed it. Except, unknown to me, it is now clear that this wasn't the first time my friend had dealt with this issue. Quickly the Skipper sprang into action. Leaving me to hang onto the loose bundle of mainsheet with one hand, and the tiller with the other, I kept us still sailing while Dick T. lashed a replacement set of double blocks onto the center thwart. This jury-rig worked pretty well, though it was now more even difficult to center the boom and the lack of a jammer made it hard upon the arms. To make things more manageable I now held the mainsheet while Dick T. helmed. Had the wind been strong handling the mainsheet this way would have been at best difficult. The next day the Skipper replaced these blocks with another set that included a jammer.

No two experienced skippers, be they cruisers or racers, are going to agree one hundred percent on how a boat should be set up. While I'm admittedly critical of this aspect of "Yellow Misfit's" arrangement, this is only my opinion. The real point is that there's a lesson here--'if in doubt fix it first'. In spite of our oversight (I accept that there was dual culpability in this instance) I give Dick Tyrrell high marks for his otherwise outstanding preparedness. He certainly was well equipped with a more than ample backup spare parts and emergency equipment. "Yellow Misfit" was ready for the passage, carrying a large supply of emergency flares, two radios, two GPSs, a masthead radar reflector, a masthead self inflating buoyancy bag, three anchors, a high powered spotlight, emergency rations--and the list goes on. The freeze-dried emergency rations would likewise come in handy when later on it was discovered (ah, there's that nagging feeling again!) that one of the food boxes had been left behind. The good news is that at least some of the emergency rations were not all that bad plus, as reports have it, Alice ate well!

We had hardly missed a beat. If Graeme and Pam were the wiser to our troubles they surely didn't let on. We were having fun again and before long the two dinghies were well into the no-man's zone, half-way between Scotland and Ireland. Both coasts were little more than low hazy hills on the distant horizon, one before us and the other behind. On several occasions dolphins were sighted. After that I kept looking intently for more, but they apparently had gone their way. A couple of ocean-going ships negotiating the shipping channel passed at a distance, but nothing close enough to get excited about. Then for a while the wind increased, giving us a delightful 'rush' and prompting the Geddes' to briefly put a reef in "Angua's" main. Occasionally part of a wave would ship over the foredeck, but "Yellow Misfit" handled fine under a full main and the smaller cruising jib. Comfortably dressed in full waterproofs and fleeces from the start the cool air and cold sea had no effect on us.

"Angua" was the faster boat and easily kept ahead of us. Even so, the Geddes graciously stayed close rather than ranging ahead. While the wind was up we made good speed, but the fine sailing didn't last. By late afternoon the breeze was on its last hurrah. Suddenly it faded entirely, stranding us still several miles off the Belfast coast. Struggling on an oily sea under leaden sky, "Yellow Misfit" made no more than a few ripples for a wake. In the distance loomed Mew Island light, frozen on the horizon. Our destination, Donaghadee Harbor, remained indistinguishable somewhere on the low coastline. Dick T. read our progress from the GPS - 1/2 knots astern. We were losing ground! For most of the way across we had enjoyed the benefit of the ebb tide giving us a push toward our destination. Now the tide had turned and so also our fortunes. Do nothing and we would be swept northward, at an ever increasing rate, away from Donaghadee and toward Belfast Lough with its busy shipping lanes. Several minutes of agony passed by before Graeme got out the oars and began rowing. But, as the Geddes' didn't carry a motor, we did and we had no intentions of rowing. There was a brief discussion, then reluctant agreement to throw in the towel and give up the pursuit of purism in favor of a tow with Dick's motor. Attempting to row from that distance was futile. This wasn't how we wanted it to be, but it shows that when necessary even cruising folks can be practical.

Approaching Donaghadee Harbor I was amazed by the massive fortress like structure of the harbor breakwall. The high bulwark was built with huge blocks of stone each painstakingly placed upon another to form a smooth impenetrable wall against the sea. Donaghadee Harbor, though typical of many manmade harbors in this part of the world, left an indelible impression upon me. A harbor of seemingly little commercial significance today, at one time it must have been an important fishing port. Entering at low water the pillars framing the narrow opening towered above us--the tidal range being 4 meters. It is an intimidating entrance for a small boat. Threatening rain clouds overhead combined with this to impart a gloomy feeling. Sadly, this feeling would prevail for much of our visit at Donaghadee. A contributing factor would be learning that this was a town where partisan feelings ran strong, i.e., "the troubles" of Northern Ireland. For a harbor of its size there were not that many boats and they were mostly of a small and simple design, or small fishing boats. Absent were any commercial vessels or fancy yachts. The town appeared dingy and lacking any sense of vibrancy. We landed on the beach at the back of the harbor to assess the situation, as there were no mooring facilities along the stone quay.

Right on cue we were joined on the muddy flat by two gentlemen from East Down Yacht Club who had been keeping in close touch with Graeme. They became our official welcoming committee to Northern Ireland. Quickly settling formalities, Dick T. and Graeme promptly engaged them in discussion. Which would be better? Rolling the boats up the beach--it was littered with debris and stones; or attempting to tie-up alongside the rough wall of the quay? After some debate it was decided to moor along the stone wall. Needless to say this was a complicated task, considering the amount of rise and fall of the tide and the need to keep the boats fended off. But we managed thanks to a lot of rope and several large fenders. Later I would learn that many of the local yachts were kept at a nearby marina. For us, however, this would not have worked as it was a small "gated basin"--a tidal lockgate at the entrance held the water in. The marina is open only during high water, again something new to me.

A rest room stop was in order, except the public toilets were locked up for the night though it was still early evening. The one restaurant on the quay also turned us away; it was too late and they were full. Lowering our standards we turned down an alleyway toward an establishment proclaiming to be a "pub". The outside was rundown, yet to me it looked benign. However, Graeme and Dick T. approached with surprising caution, one of the two slipping in for a look first. The inside turned out to be equally shabby and dirty, with only a handful of patrons consisting of a rowdy younger crowd. In spite of this there was one bright spot. A lone older gentleman sitting at the bar took an interest in us strangers and wanted to hear our account and about the American. Certainly this was a place that experienced few outside visitors. The man, neatly dressed in a well worn suit that had seen better days, bought us all a round of beers. It struck me that he probably could ill afford this kind gesture. Nevertheless, we were uncomfortable and didn't dally long. Outside again, the lateness of the hour and the generally depressed state of things, as well as the display of partisan Protestant flags from light standards around the harbor, kept us ill at ease. So it was back to the quay and close to the boats, where we dined on carry out fish and chips for the second night in a row. The fish was superb, except that the steady diet of greasy food was getting tiring. During the night it rained hard.

Several drops landing annoyingly on my face were sufficient to bring me wide awake. A puddle, actually more than one, had formed on top of the boat tent and were dripping inside. The Tyrrells have a straight-sided style boat tent which is popular among the English. The sides are made straight by using the oars to create additional side ridge poles. They are attached to the shrouds and a collapsible frame that sets upon the transom. This makes a cabin that is much roomier than the single ridge pole 'A' style tent that I use in the U.S. The flat top, however, can pocket rainwater and when the fabric begins to get tired the puddles become a nuisance. By now my sleeping bag had a couple of wet spots. Fortunately, thanks to the Tyrrells whom provided me with sleeping gear as well as a few other items for this adventure, it was a good quality synthetic fiber bag and not greatly effected by wetness. The sun, though hidden by a heavy overcast, had been up for a while. The rain was easing off and a cup of coffee would be welcome. Following a good night's sleep Donaghadee looked much more cheerful and a block away was a fantastic bakery serving breakfast. Before long I was joined by the rest of the group and we gorged ourselves on the house specialty, the "Ulster Fry"--eggs, back bacon, sausages, fried tomatoes, toast and fried soda bread. Stuffing the leftovers into our pockets we added a purchase of sweet cakes for later. Upon discovering the missing food box we would be happy we did this. Following a much needed refreshing shower, thanks to the kindness of the local sailing club and Dick T.'s public relations acumen, we were ready to head out again. Here it should be said that my Skipper's unique and rare talent for acquiring friends and making acquaintances was a invaluable asset throughout the cruise.

"Winds cyclonic--sounds just like yesterday." Graeme was relaying the weather report. It was nearing midday and high tide. I thought that Graeme Geddes exhibited outstanding style as a cruise leader and have vowed trying to emulate some of his ways the next time I'm in such a position. He always took plenty of time before departing to go over the day's sailing plan and he solicited input. Once underway he was meticulous about not getting too far out front, staying within hailing distance most of the time. For the time being the rain had stopped. The forecast was for winds force 3 to 4 later, but at the moment there wasn't any. Graeme continued the briefing. "I suggest that we make today an easy sail and look for a place to stay overnight by early afternoon." He was thinking of Pam and myself, I believe. Catching high tide we would have the current with us. Graeme's thoughts were that we should look for a protected stretch of sandy beach to bring the boats ashore, there being few places along this section of coast suitable for anchoring. The port of Portavogie should be avoided as it is a busy commercial fishing port and would not be pleased to welcome us, except in an emergency of course. By my calculation the distance from Donaghadee to the entrance buoy off Strangford Lough was only 22-1/2 nautical miles, yet Graeme didn't anticipate arriving before Wednesday morning, or possibly not until a day later. I thought this to be ultra-conservative and that such a sail couldn't require two days. It seemed with good weather we should get there sooner, however, I would learn differently.

I never imagined it would be this way, but there we were the second day out again motoring and towing "Angua" behind. Back home in Ohio my mind had painted a picture of what it would be like making our way south along the Belfast coast. The strong prevailing southerly would be blowing and our little boats would be pitted against steep sided waves, hunkered down under reefed sails. We might even have to be working the bilge pump. On this day the Irish Sea was uncharacteristic of everything I had expected. In this sense I was disappointed, but not wanting to tempt fate I kept such thoughts to myself. Surely things would change soon. A long dark band of clouds lay a short distance inland. We could see the rain coming down. An invisible sea breeze above held the rain clouds motionless, giving those beneath a soaking. Yet for us there was hardly a breath of air. We had started out under sail, but soon the Skipper was grumbling. "Do we just sit here drifting with the tide, return to Dunaghadee, or try to make some distance toward our destination?" Dick T. didn't mind putting up with the drone of the motor in his ear and he had several containers of gasoline--enough for quite a bit of motoring. I also was for pushing on, knowing that Margie anxiously awaited my return by Wednesday at East Down Yacht Club. Graeme's prediction of possibly being a day late hadn't set too well. Spending another day in Dunaghadee with little to do held no attraction for any of us. So one more time we coerced the Geddes' to accept a tow. On flat water and traveling in a straight line, with the tide helping, we were making good progress. I occupied myself gazing at the scenery along the Belfast coast. Gradually but surely it passed astern. Then there were the antics of the seabirds too. Long periods went by without either of us speaking, the noise of the motor making conversation difficult.

The Belfast coast is low and not as appealing as Scotland's, but it is far from boring. Passing near the coastal towns only a short distance off shore we could see marvelous stone castles and cathedrals. Standing unmistakably on a distant high hill was the proud sentinel, Hellens Tower. This was the Irish Coast, settled in ancient times by the Celts, Vikings and Normans, and I was sailing the waters where Vikings once roamed. At one point we came upon an impressive palatial seaside estate. The Skipper explained that it dated back to a period when this locality was a popular place for monarchs and royalty to spend summer holidays. At Ballwater we swung outside of some off-lying ledges, then laid a line for Burr Point. Ballyhalber Bay, with its long sandy beaches appeared in the distance.

By the time we were motoring through the slot inside Burial Island off Burr Point a couple of hours had elapsed. The land and seascape began to take on a more interesting character. We were encountering rocky reefs extending far out from shore, and there were frequent and long meandering strings of fishing pots for crab and lobster blocking our way. It was necessary to stay alert and keep on the lookout for the fisherman's marks. If it had been windy I might have been nervous about the possibility of getting snagged in one of the lines and maybe capsizing. They seemed to lie just beneath the surface waiting to catch a centerboard or rudder. In another hour we were approaching Portavogie. A mile or two, to the outside were four or five large fishing boats, scallop draggers working in big semicircular tracks. The booms for the mammoth bottom drags, one off each side of the vessel, came up and the nets emptied, then let back down. Billowing plumes of black diesel smoke emitted from the vessel's dual stacks as the operator again hit the throttles and the props dug in. Graeme, getting antsy, signaled for us to hold up. We had pushed further than intended and it was getting late. It was time to look in earnest for a place to beach the boats.

None of us of course had sailed this coast before, so this was a learning experience for everyone. The strongly fortified harbors I'd seen had me convinced that this was no place to be taken lightly. We needed substantial seaward protection. The area around Portavogie appeared to offer a few prospects as there were many reefs and several small low lying rocky islands close to shore. But trying work our way inside the reefs didn't look easy and nothing popped out as particularly attractive. About half a mile south of Portavogie is a rocky ledge and cluster of rocks called North Rocks. Sneaking in behind this looked more promising. "There's not much water, but the chart shows half a meter over the bar", were my words to the Skipper, as we headed into a 'rock garden'. It was nearing the 18:00 hour and low water.

The reef offered fair protection from the sea, but the beach consisted of far more rocks and kelp than sand. The path, as it were, for rolling the boats up the beach above high tide was long and torturous. It would be very difficult. (Actually, we would soon learn attempting to roll the boats in any manner whatsoever was next to impossible.) Lying to an anchor was questionable as well because of so much kelp and rock. Regardless, for the time being our path to explore further was blocked. I had misread the chart! The 1/2 meter designation was the drying height of the bar, not the depth of water. A couple hundred meters away we could see overfalls on the bar. My face was red. While contemplating the next move it was decided to have dinner (our first adventure with the emergency rations!) and wait for the flood tide to cover the bar. Meanwhile, a man from a nearby house came picking his way down the beach toward us. Were we about to be evicted? Maybe he was the fisherman whose pots we had struggled trying not to entangle on the way in. Introducing ourselves we explained that we were thinking of spending the night. "This here is not a very good place", was the man's reply. His voice sounded sincere and I detected no sense of hostility in his manner. "You're welcome to stay, but most folks go to Cloghy Bay. I think you'll find that more to your liking", he suggested. Cloghy Bay was half a mile further on the other side of the bar. Evening was fast approaching.

An hour later the distant wall of tumbling water had subsided to the point where it appeared as no more than a narrow dark line of disturbed water on the flat surface of the sea. We were too far away to pick out possible gaps, but decided that it was time to get going as daylight would soon be gone. I was confident that even towing "Angua" we would have little trouble punching through what now looked like a small wave. "I'm going to approach slowly and probe," the Skipper advised. With the sea water being cold and clear we were able to see the bottom easily. Nearing the bar I watched as the rocks on the bottom got closer, but judged there was still plenty of depth. "We're doing fine," I said, as Dick T. cut the throttle to a crawl, then turned broadside to the bar. The obvious assumption on everyone's part was that because the tide was flooding the water would be coming over the bar at us. This was a blunder! "Dick, watch out, we're being drawn in!", I shouted too late. Being the one forward I could see what was about to befall us. Helplessly over we went, dragging "Angua" behind, our hearts suddenly in our throats. Luck was with us. The depth was sufficient and the drop but a minor thrill. The lessen, however, was sobering. Around unfamiliar reefs and bars one should never assume to know which way the current is flowing. Under different circumstances the consequences of our oversight could have been much more frightening.

Cloghy Bay is exposed to the open sea from the east and north. On the other hand the beach is mostly hard sand and smooth. Some sparse protection is afforded by a small point jutting out from the south end of the bay. Dusk was upon us and it was starting to drizzle. We were in the position we had sought to avoid--out of time and places to go. We would have to make the best of it and roll the boats above high water, under the crook of the point as much as possible. The Geddes' carried two large inflatable rollers and "Yellow Misfit" two oversize boat fenders. The rolling team consisted of two men, one woman, and a 65-year-old, which was me. Struggling mightily we got "Yellow Misfit" at most a few meters up the sand before giving up. The high water mark was 100 meters or more to go and we weren't going to make it. How the British routinely roll their Wayfarers up beaches will remain a mystery to me. The next hour and a half was spent working with the tide, moving anchors and walking the boats up the beach. A soaking drizzle combined with the cold sea water on bare legs made this a bone chilling chore. It was an unpleasant task which fell for the most part upon Dick T. as I erected the boat tent and dried things out. At last satisfied that we were safe the Skipper set the anchor, then fell aboard exhausted. Everyone slept soundly that night, comforted in part by knowing that we had covered a lot ground and were in good shape for making Strangford Lough on schedule.

Upon waking my spirits were greatly uplifted. The rain had stopped and the sun was actually trying to break through the clouds. Cloghy beach was quite a pleasant place. "Yellow Misfit" and "Angua" sat high and dry on the sand, yet so level and comfortable that I had never noticed when ground took the place of water. Setting the Coleman gas stove on some nearby rocks, Pam announced she was cooking breakfast for everyone. Thank goodness, as Dick T. had ruled the reconstituted scrambled eggs from the night before uneatable. "Yellow Misfit's" foredeck made a handy breakfast table. The tiny hamlet of Cloghy was only about 3/4 of a mile away along the quiet shore road. It made for an enjoyable morning excursion and a small corner store provided a chance to pick up a few meager food items. By mid-morning several of the gang from EDYC showed up checking on us, this time in one of the club's "RIBs" (Rigid Inflatable Boat). Graeme had continued to keep in touch with them, as well as with Alice and Margie, via cell phone. The "RIB", a husky craft capable of taking plenty of rough water, was fast and the fellows had made the run all the way from the club. They would be back the next day (Wednesday) to escort us up the entrance to Strangford Lough--the narrows.

On our third day out the Irish Sea continued to challenge us, but still not in the manner I had anticipated. The sea was tranquil, ruffled only by small wavelets. Nevertheless the presence of some wind enabled us to raise sail. Close in rounding the Cloghy Bay point I noticed more changes in the character of the coast. The rocks along the shore were taking on a menacing appearance. "Man, look at those dragon teeth", I exclaimed to Dick T. A vessel, large or small, coming upon those razor sharp outcroppings would be doomed within a matter of minutes. Sometime in Ireland's geological past forces worked to turn great slabs of granite on edge, creating long jagged ridges that became reefs running out into the sea. There must have been softer veins, possibly different minerals imbedded in the rock, which eventually wore away due to the action of the sea leaving behind sharp needle-like structures. It was striking. I have seen lots of rocky shores before, but this was different and it fascinated me. The scenery in general was becoming more interesting the closer we got to the 'big lough'. A few low hills, with wooded patches here and there, were beginning to evolve and lush green meadows ran down to the edge of the sea. Under the gentle breeze we leisurely glided along the shore taking in the sights, not worried a whole lot about covering very much distance. This day we only planned to make four or five miles. On the other side of Kearney Point an unexpected surprise awaited--a magnificent castle built right at the water's edge. What a splendid photo opportunity.

Two small bays lie between Kearney Point and the next point, shown on the chart as Pilot Lookout. With luck we would find a place to beach the boats in one of the bays. This would put us within two or three miles of the entrance to the lough. Faintly at first, but gradually increasing in volume, the unmistakable sound of children at play came drifting across the water. The cove we were headed toward contained a cluster of three or four houses and a couple of beached boats. One small fishing boat swung on a mooring. The voices of the children became a bellow. "Oh, no!", Dick T. groaned. I hadn't yet caught on and didn't understand the reason for his pain. Then I heard it. "Give us a ride!" "Can we have a ride?", the youngsters were yelling. When we landed at the narrow stone jetty behind the nearest cottage there were four children of various ages gleefully running down to greet us.

Following some investigation we concluded this spot to be the best, though endowed with much rock there was also some sand. The woman who owned the house was away, but expected back soon. We would need to anchor out, yet still wanted to be sure we wouldn't be intruding. For the time being since it was high water we moored the Wayfarers alongside the jetty. Seeing that I didn't mind, the Skipper quickly abandoned ship leaving me with the boisterous youngsters. Putting the two youngest, a boy and girl about four and five years of age aboard, I showed them how to operate the bilge pump and work the tiller. However, when the boat rocked a trifle their faces registered worried looks and they decided that being tied to the jetty was okay. Presently a neighbor, a mother presumably, arrived offering tea and biscuits. She was no doubt delighted for the temporary reprieve from watching over the urchins.

The homeowner turned out to be a naturalist with a university in Belfast. In a miniature penned-in pool behind the house were two juvenile harbor seals which had been rescued following a storm. The pups, temporary pets, were cute and playful keeping us occupied taking pictures for some time. We enjoyed a very hospitable visit that even included use of the house bath. However, upon learning that I was an American I did get to feel some heat. The poor woman was convinced that within a decade or so, rising sea levels resulting from global warming and melting of the polar ice-cap were destined to inundate her home. I found it difficult defending our Government's policy for refusing to sign the "Kayto Agreement". We parted friends and I felt that it had been a good experience to have to deal with such questioning.

The cove was surrounded by razor sharp outcroppings with barely enough room for the two boats. In addition, the considerable tide meant we needed lots of swinging room. Two times we set the anchor, warily keeping an eye on nearby rocks and checking for dragging. Following dinner (yes, it was emergency rations!) we turned into our sleeping bags, but lay awake. The Skipper flicked on the compass light and watched the swing of the compass card, guarding against a change that might call for a look outside in the dark. In the stillness I listened to the burble of water passing along the hull and the noisy wash of waves over rocks just astern. The rocks sounded much too close. Eventually I dosed off only to awaken again when the wind or tide switched, causing the motion of the boat or sounds to change. When morning arrived we were anxious to get underway, but forced to wait patiently for low water.

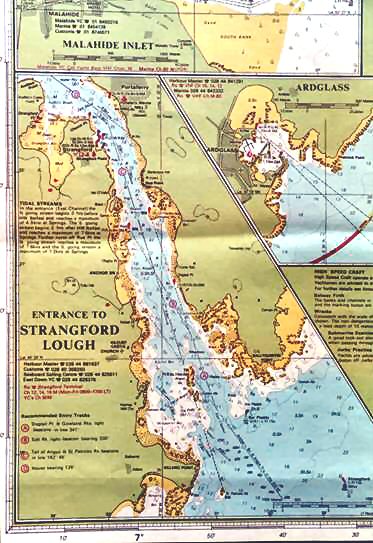

The entrance to Strangford Lough is challenging. Initially I had no concept of how treacherous it could be. As time elapsed and I began receiving details from Graeme Geddes and Dick Tyrrell it became apparent that this would be a whole new experience. To appreciate the magnitude of difficulty posed by this entrance without experiencing it is hard. I'm convinced that the reason those magnificent voyageurs, the Vikings, named the lough "angry waters" is because of the entrance and not the lough itself. I looked forward to the challenge, but I felt apprehension as well.

The narrows vary between 1/4 to 1/2 mile wide and are 5 miles long. Behind this lies the large deep body of the lough itself, which is 5 miles wide by 20 miles long. Twice daily the sea flows into and out of the lough through this one entrance. During Spring tides, the period of highest tides, the coastal tidal range is 4 meters (13 feet) and the lough's tidal range reaches 3 meters (10 feet). At these times the speed of the current in the channel reaches 7.5 knots. The enormous volume of water passing through the narrows possesses tremendous energy with some of it being manifested in large standing waves, known as overfalls. Overfalls occur where the current meets the ocean and can extend for a considerable distance off the entrance. At peak it can easily swamp a much larger vessel than a Wayfarer. One local sailor told me that in the right conditions, with wind against tide, the waves can obtain heights as great as 20 feet. These are not ocean swells, but steep-sided breaking waves. The only time when it is truly safe for a small vessel to enter is during slack water. Graeme's strategy was to time our arrival just after slack low water, then sail up the entrance on the flood tide. Still, depending upon wind conditions, there was no guarantee we wouldn't experience rough water. The tide was at "Springs", the worse condition.

It was time for a conference, though much had already been discussed before. "The 'pilot' states that a safe time to enter is one hour following low tide", Graeme was saying. He was cautioning about arriving too early. Dick T. interjected, "the e-mail from your EDYC contact suggests two hours after." Just the same Graeme would stick by the 'pilot', which was fine by us. The sun was out, at least partially, and from inside the cove we could see that finally a breeze was blowing. The outlook was nicer than anything we'd experienced the last couple of days. Graeme's opinion was that by the time we got around to the entrance the wind would be onshore, while I was certain that it would be offshore and on our nose. It made a difference. If the wind was onshore any overfalls would be made rougher, whereas an offshore wind posed less of a problem but meant a five-mile beat up the narrows.

Approaching the entrance to Strangford Lough we were in the lead. Upon entering we wanted to round close to the Cardinal Mark on Bar Pladdy, off Ballyquintin Point, and keep to the near shore. Ahead and a ways off I could see three buoys, or beacons, but couldn't tell what they were. (In this locality both the 'Cardinal Spar' marks, as well as the international 'can & nun' buoyage system, is employed.) "I think we've still got a distance to go", I said to Dick T., while searching for the elusive Bar Pladdy Cardinal. Just then the Skipper spotted the big stone pylon inside the entrance to the narrows and there to its right was the Cardinal. We had nearly sailed past it. I was chagrined. On the other hand, the wind was blowing straight down the channel and smack on our nose, just as I had anticipated.

The two skippers, Graeme and Dick T., had figured it perfectly. Entering the dreaded 'dragon's mouth' we encountered little in the way of rough water, though much swirling and churning current. The tidal stream had already reversed. On this day our concerns proved to be unfounded. One could easily have been fooled by the serenity of the moment. However, we weren't home yet. Before us lay a five-mile beat up an unfamiliar channel. Soon the Wayfarer World overtook us and the "two Dicks" were once more looking at "Angua's" stern. Clear blue waters sparkling under a sunny sky, combined with marvelous scenery and a good breeze, to make sailing everything one could ask for. And for a while the scene was all ours, just the two Wayfarers with no other boats in sight, adding to the sense of adventure. On our right a low rocky shore backed up to small hills with green meadows. It was sparsely populated with a just few houses scattered here and there. To our left the village of Kilclief, a small cluster of houses, nestled around the foot of Castle Kilclief towering over all. Hiking-out to keep "Yellow Misfit" flat and at the same time help watch for shoals and sharp ledges, I still managed to snap some photos.

After a couple tacks we were met by the EDYC "RIB" crew, which this time also included Alice with camera. Briefly they circled us for some photo taking. Half-way up a large whirlpool was encountered and successfully traversed. This is always a weird feeling--like there's something below waiting to get you. The current had increased noticeably. With the shoreline flying by sailing a straight course was taking all the Skipper's skill, however, any lingering doubts about being able to make it all the way were dispelled. A mile further up are the picturesque towns of Strangford on the west bank and Portaferry on the east bank. This is a busy ferry crossing. At the mercy of the current the Skipper had to steer with great caution to avoid the paths of the two ferries plying back and forth between the towns. There is less than 3/4 of a mile to go. Exiting into the lough Dick T. had a moment to check our speed over ground with the GPS. As I recall it was 7-1/2 knots! Having failed to keep good track of our time I can only guess, but I think the whole trek up the narrows didn't take much more than an hour.

Catapulted into Strangford Lough like a cork riding the crest of a wave, suddenly less than three miles off is the town of Killyleagh, its church spires and great castle in full view. Bearing down to greet us and waving cheerfully are Wayfarer friends from England, Denmark and Ireland. We wave back, abruptly aware of how quickly this awesome adventure is coming to a close. Only four days ago we started out to cross the Irish Sea. In an hour we will be landing at the East Down Yacht Club dock. In between so much has transpired--what an experience!

Despite the fact the cruise was done this was not the end of our adventure. Still to come would be several more days of wonderful sailing on beautiful Strangford Lough--this time with the larger group of friends attending the rally and with my favorite companion, Margie, by my side. The wind would blow strong, but not too strong. There would be an occasional rain shower, but by the norms of Irish weather sunshine was plentiful. We would pack a day lunch, maybe include a couple pints of beer or a bottle of wine, then head out by boat to some magical location. One such excursion would find us visiting the ancient ruins of the Monastery of St. Mochaoi Nendrum on Mahee Island, a ringed monastic enclave dating back to 400 AD. Brian Williams, an Irish Wayfarer who is the project manager of the dig and chief archeologist for Northern Ireland, would lead our group on a very special tour.

For Margie and I the short time we spent in Northern Ireland was a once in a life time experience, one from which we shall always hold many cherished memories. We are deeply grateful to all of the Irish Wayfarers and EDYC for making this event possible. A special thank you goes to all of our international Wayfarer friends, particularly Alice and Dick Tyrrell and Pam and Graeme Geddess, who hosted us and made it possible for us to enjoy such a terrific adventure. The End - Dick Harrington copyright © 2002 |

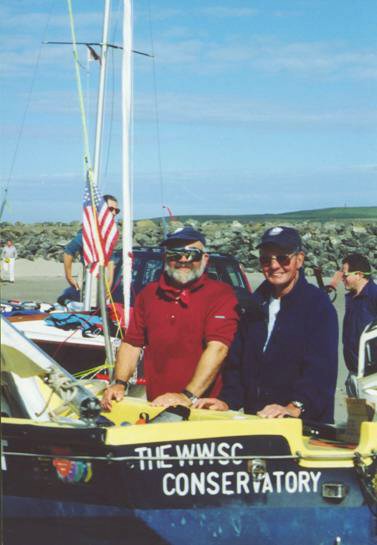

Photo Captions  Chart of the Irish Sea.  2 Tourist map "The Kingdoms of Down" is a good illustration of the Belfast Coast and Strangford Lough.  3 Chart inset of the entrance to Strangford Lough.  4 Margie Harrington on the train from Dublin to Belfast.  5 Dick Harrington at the forward windows of the HSS Stena.  6 Left to right--Dick Tyrrell, Graeme and Pam Geddes, and Margie. Graeme and Pam spent the night on the beach at Port Logan.  7 Sunday morning at Port Logan preparing to depart.  8 The "two Dicks"--left is Skipper, Dick T., and right Dick H.  9 Alice Tyrrell.  10 Left to right, Pam and Margie.  11 The Geddes' raise the mainsail.  12 The Skipper checks the rudder.  13 The Wayfarer World heads out.  14 "Yellow Misfit" follows suit.  15 The Scottish coast viewed in the direction of Port Logan.  16 The wind picks up prompting the Geddes' to put in a reef.  17 The fortress like structure of the Donaghadee Harbor is typical of many man-made harbors in this part of the world.  18 For a harbor of its size there were not that many boats.  19 Moored alongside the stone quay at Donaghadee.  20 Cloghy Beach was quite a pleasant place.  21 Thank goodness, Pam announced that she was cooking breakfast for everyone.  22 A surprise--a magnificent castle built right at the water's edge.  23 We landed at the narrow stone jetty behind the nearest cottage.  24 In a miniature penned-in pool there were two juvenile harbor seals.  25 We were surrounded by razor sharp outcroppings with barely enough room for the two boats.  26 The entrance to Stranghford Lough was deceptively serene this day.  27 We are met by the EDYC "RIB" crew which this time also included Alice with camera.  28 Castle Kilclief towers over the village of Kilclief.  29 The picturesque town of Strangford.  30 At the mercy of the current the Skipper had to steer with great caution to avoid the paths of the ferries.  31 The cruise is done but this is not the end of our adventure. |